Akira Kurosawa made film history with masterpieces like “The Seven Samurai.” Naturally, his filmography has inspired the next generation of filmmakers.

Mitsuhiko Kawamura is one of them. He picked up his camera as soon as he saw Kurosawa, and fate would guide him to the film set of Kurosawa’s life work “Ran.” There, he captured on camera, the master engaged in his craft.

Cruel fate intervened, however, as he was prevented from using his footage. While he was producing “The Making of Ran”, as a company independent from Kurosawa’s, the President of Kurosawa Enterprise asserted legal rights over the tapes, seizing them from Mr. Kawamura.

It took four decades for Kawamura to recover the footages and release them as the documentary film “The Lifework of Akira Kurosawa.” I asked him about this achievement that spanned across his lifetime.

“Before I met Kurosawa, I was a youthful aspiring director who dreamed of making films like Kurosawa. Now, I am 61 years old.” Despite his self-deprecation, his eyes were still beaming with the same hopes that were ignited when he first encountered cinema.

Exclusive: Free Streaming of “Lifework of Akira Kurosawa”

Mr. Kawamura has provided a streaming link exclusively for this website’s readers.

In the “Lifework of Akira Kurosawa,” you can witness Kurosawa engaged in his craft.

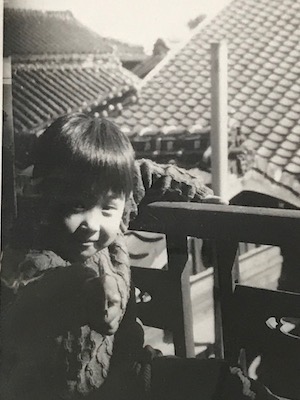

Enchanted by Cinema

Mr. Kawamura as a child

When I was little, I begged my mother to take me to the monster movies, like “Godzilla,” and “Gamera.” In 6th grade, I met Bruce Lee in “Enter the Dragon,” and I had to meet him again. I watched it about 10 times. As I began to attend the movies by myself, I encountered Alain Delon, Luchino Visconti, and Federico Fellini, as well as their American counterparts in “Poseidon Adventure” and “Jaws.”

I saw “The Seven Samurai” in 9th grade. I enjoyed it, but it was not until I saw “Yojimbo” and “Sanjuro” on TV that I wanted to become a film director. Never have I seen such fast-paced Japanese films.

I wanted to learn how Akira Kurosawa became a director. He advised others that “It’s pointless to go to film school. If you want to direct movies, you have to study how people grow to decide between good and evil.”

Mr. Kawamura studying to get into college

I got into the university that I had applied for during my gap year. I walked into the film club as soon as the entrance ceremony ended. But I quit when I learned that they didn’t make films on 8 millimeter.

A year later, one of my seniors approached me to make a film. I was chosen for the starring role; probably because I looked better and was 40 kg lighter than I am now. During filming, I learned that movies were made one shot at a time. And that’s when I felt that I could direct. I based my first film on the biggest heartbreak in my life during my first year of college. Wondering how I could get Kurosawa to see this, I submitted it to an 8 millimeter film contest. However, it didn’t get accepted, so I gave up.

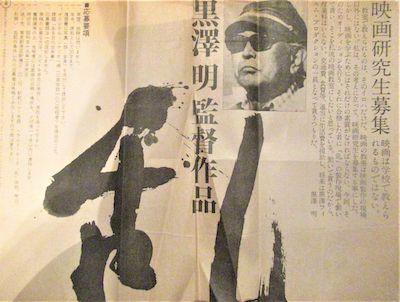

Rejected by Kurosawa, Accepted by Kurosawa

Kurosawa had announced the production of “Ran,” and began looking for assistant directors. He would pick 3 people to train on set based on your story submission about “something that happened one day.” This was my chance. I had to get accepted for this.

I was sure God would give me this opportunity, but again I didn’t get accepted. However, I got a phone call around the same time. I would not forget this fateful June 1st.

“I am producing a Behind the Scenes of Akira Kurosawa’s ‘Ran.’ We need some help. Do you want to do it?”

It was from a friend of another director whose film I had starred in. This guy was a film fanatic who worked at a video store. When he brought this idea to the production company Herald Ace, they liked it. There was 1 year until “Ran” hit the theaters. During that one year, everyday felt like a dream.

Meeting Kurosawa

I arrived at the Himeji castle set the day before filming. I was introduced to Kurosawa in the hotel lobby. This was my dream come true. But I thought that if I showed how excited I was, I would be belittled as a professional. So I had to suppress my jubilation when I shook hands with him. Looking back, I had squandered an opportunity. I should have shown him how thrilled I was to meet him. Instead, I had probably made a rude impression.

An Ageless Kurosawa

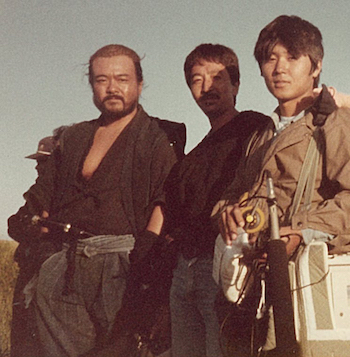

From right: Actor Masayuki Yui, Camera Hiroyuki Taniguchi, and Mr. Kawamura himself

Filming began the next day. There were about 100 people on set. Kurosawa was 74 years old at the time, but he didn’t hesitate to give orders. He would decide on the camera position and place the assistant directors as stand-ins. He would be standing with the actors and recite their lines. “Stop here.” “Say this and run there.” “Respond to this line like this.” He even rehearsed with the supporting actors, including the dozens of elder aides. When he instructed the role of the jester played by Peter, he became delighted by his more comical renditions. I learned by following his directing for over 100 days.

He gave no direction to our video crew, but advised us a couple times. “You should take a bird-eye view here.” “You should film behind the cameras.” We made sure we didn’t interrupt his crew, who trusted us and let us stay on the set.

The French Connection

Mr. Kawamura holding the mic on set

The crew were building the castle for its immolation at the end of October. Another documentary crew led by Chris Marker entered the set for just a month. Unlike amateurs like us, they had professional cameras and audio. The director gave instructions actively.

They showed little consideration for the crew. As the crew carried rails for the cameras, they poked their heads between the gaps. We were shocked, as we had done everything to avoid getting on the nerves of Kurosawa’s crew.

Only when I saw the completed film “A.K.” did I realize that they decided on several themes on set to help organize their footage. Their film did well at depicting the Kurosawa crew, supporting each other beyond their assigned roles.

No other crews were permitted to visit the set. Media access was permitted only during the two days when we filmed the battle scenes. When TV shows needed more footage from the set, we provided them.

The Long Goodbye

After one year of filming, we had 150 hours of footage to edit and release publicly.

This ‘behind the scenes’ footage was self-financed out of our own pockets, without any sponsorship from Herald Ace or Kurosawa Production. We bought the video tapes and camera, and borrowed money from Herald Ace for accommodation. To return the debt, we first made a program for Fuji TV (one of Japan’s many TV Station). We planned to edit the footage based on that.

Then came Kurosawa Enterprises.

“You have no rights to edit this footage,” they said. If Kurosawa appeared on film, they claimed legal rights for full editorial control. With that, they took away our 150 hours of footage.

We felt that we couldn’t argue against Kurosawa Productions. This is a common misconception, but do the subjects being filmed have rights to edit the footage? If the Prime Minister, or a subject of a popular news subject, or Kurosawa himself got filmed, would they have the rights to edit their respective footage? But back then, I couldn’t think of such arguments to refute back at them.

Ranta Kawamura, then-president of Kurosawa Enterprises, states in his memoir that he seized them legally. In actuality, this legality is questionable.

Kurosawa Enterprises would later release “The Making of Ran,” produced by Hisao Kurosawa. During its production, our crew were not consulted. It would’ve been difficult to skim through 150 hours of footage for the first time, let alone organize them into a single film.

“The Making of Ran” was released in 1985 as VHS. It quickly became out-of-print as it wasn’t well-received. It was forgotten until it was re-released as one of the many installments in Toho’s Kurosawa DVD collection.

When they took away our footage, we relented only because we hoped they would improve upon what we had filmed for over a year. It was painful not to be part of its production. However, I was at least able to learn about filmmaking from the Kurosawa crew. Now it was time to think how I could become a film director.

I’m in Showbiz, but…

I arrived in Tokyo to work in showbiz. Through an introduction from a member of the Kurosawa crew, I started working as a unit director of a news program. It was 1985 – a year rife with salacious news.

But it wasn’t what I really wanted to do, so I quit after 6 months. I began work as an assistant director of a TV drama the following year. Of course, I can’t compare it to the Kurosawa crew, but it was stimulating to work under the constraints of a budget, schedule, and staff. I continued working in this position for 2 years.

Being on a film set alone is exciting enough. But that doesn’t always contribute to producing great works. If you can’t divorce yourself from the excitement of the film set and the quality of the finished film, you end up producing a boring film. I began to question what I was doing at my job. And I recalled what I had read from Kurosawa when I was 19: “If you want to direct movies, you have to study how people grow.”

That’s why I set foot into a new genre of “Medical Movies” where doctors can learn how to treat infectious diseases with the latest cures. For instance, I filmed a mouse body under a microscope, and presented the movement of white blood cells over a day as a time-lapse in 30 seconds.

Later upon being contacted by a film crew that specialized in jungles, I produced a “Science Movie” that captured the beauty of Mt. Fuji from every angle, during the four seasons. The cloud would rise above the mountain, and the sunset would bleach the sky in crimson. The budget was about 200 million yen, and the film was taken in 70 millimeters for projection in planetariums.

Reunited with the Archive Tapes

Archive tapes spanning across several carboard boxes for storage

Kurosawa passed away in 1998. At his memorial service, Satoru Iseki, the producer who helped us the most for our filming, told us that he found the footage. Until then, we thought the tapes were in limbo.

Re-watching the footage from the set of “Ran” reminded me of the days we toiled to create our best work.

Now the tapes were back, but the U-matic tapes we used back then were unplayable due to the video format’s obsolescence. We had to transfer them to another format called betacam. However, we couldn’t afford to buy all the betacam tapes for each original tape. Film digitization was gaining traction in the United States, but we also couldn’t afford to carry 450 tapes abroad. Meanwhile back in Japan, there was no such initiative.

No Time to Die

As I produced “Medical Movies” and “Science Movies,” I lost the opportunity to produce narrative features. On the other hand, I had the Kurosawa video tapes, but I couldn’t use them.

It was now 2020.

I had stomach cancer. At the same time, COVID broke out. I heard that cancer treatment reduces immunity, so I believed that contracting COVID would lead to my instant death. In Kurosaawa’s “Ikiru,” the protagonist ponders what he can do within his remaining days. I found myself in his shoes, contemplating on my death for the first 2 days after my diagnosis. Later my doctor told me not to be so pessimistic, as the cancer was discovered early, and that cancer had become more treatable since the days of “Ikiru.”

What I learned from “Ikiru” is the emptiness of spending your remaining time in hedonism. I saw the protagonist use his last days to do something meaningful.

“What can I do during my remaining days?” I pondered during the first 2 days following my diagnosis. Even if I had to go into debt, I wouldn’t want to make a narrative feature. Instead, I wanted to release our footage as a documentary and testament to the legacy of Kurosawa

I had no desire to make a documentary since I got the tapes back in 1998. It was better to leave the tapes publicly available for viewing without any editing. So I wanted to release them on YouTube to have them seen like a live broadcast.

Overcoming Backlash from the Kurosawa Crew

It turns out that only 70 hours out of 150 hours were returned to us. As digital transfers to DVD became less pricey by then, I took out a loan to digitize them. The loan far exceeded my income back then, but I managed to transfer the tapes in one year and start uploading them on YouTube in 2006.

There is a misunderstandings where people believed that Kurosawa behaved like a dictator on set, exploiting his staff and squandering the budget. I could not forgive that. Some film critics capitalized on his death by publishing timely books, and even derisively called him “Emperor Kurosawa.” I wanted people to know that Kurosawa’s film set was more cooperative.

Kurosawa’s manager Teruo Nogami interviewed me upon the release of “Making of Ran” on DVD in 2006. I told her about my dream to publish the footage on YouTube for the world to learn about Kurosawa’s filmmaking for the next generation of filmmakers. Nogami, who knew Kurosawa very well, responded like this.

“Your videos are not going to produce a genius like Kurosawa.”

I believe she felt that it’s presumptuous to aspire to make films like Kurosawa. Even Takashi Koizumi, who served as assistant director for Kurosawa after “Ran,” felt that the video was pointless. Honestly, I was shocked.

But it was Kurosawa who had called for assistant directors on “Ran” to show his filmmaking, and had allowed us to film him behind the scenes, hoping that the footage would be be useful for future filmmakers. I believe that the footage will help filmmakers realize how a director should perform his craft.

What is Cinema?

Film art does not simply exist to stimulate your five senses for fleeting sensations like a roller coaster ride. It allows you to encounter people and circumstances outside of your daily life. That’s the value of cinema.

Film directors are not mere employees of the studio. They point their cameras to crop out spaces from the film set and provide audiences an experience of a lifetime. That was what I learned from the set of “Ran.” In a way, you reenact God’s act of creation when you make movies. In the end, film exists to help people grow.

The interview footage is currently being edited as a short documentary. A preview was screened at a theater in Tokyo.

Stay tuned for further updates.

Staff

Director: Richard Rowland

Cinematography: Erjol Muarem

Sound/Stills: Michael Herrington

Edit/Grading: Richard Rowland

More interviews...

Richard Rowland

Latest posts by Richard Rowland (see all)

- Python Conference Chairman: Building a Programming Community, One Coder at a Time - March 5, 2023

- Searching for Kurosawa – Why I took 38 Years to Release His Footage - February 6, 2023

- Internet Pioneers Place Next Bet on Blockchain - August 13, 2016